Principle First:

Communication /kuh · myoo · nuh · kay · shn/ noun.

A process by which 1 person makes his or her thoughts and knowledge understood by another person.

A team needs to communicate to create shared understanding and to coordinate actions. Communication is an important aspect of Psychological Safety.

A mentor of mine once described communication challenges as caused by passing through 4 filters:

- What you meant

- What you actually said

- What they heard

- What they think you meant

There are defects on both the transmit and receive sides.

Stephen Covey developed “The Five Levels of Listening” in his book The 7 Habits of Highly Successful People.

This model outlines the different levels at which listening can occur:

- Ignoring: Not listening at all.

- Pretending: Acting like you’re listening but not really paying attention.

- Selective Listening: Hearing only parts of the conversation.

- Attentive Listening: Focusing on the speaker and paying close attention.

- Empathic Listening: Understanding the speaker’s perspective and emotions deeply.

This week’s story will show the challenges of comprehension are in fundamental differences in the way different people perceive reality. And this week’s framework will offer help.

🧠 Today’s Framework: Active Listening

📚Today’s Story: A Mental Model for Counting

📝 Today’s Quotes:

Effective teamwork begins and ends with communication.

- Mike Krzyzewski, Basketball Coach

The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.

- George Bernard Shaw, Playwright

To effectively communicate, we must realize that we are all different in the way we perceive the world and use this understanding as a guide to our communication with others.

- Tony Robbins, Business guru

🧠 Today’s Framework: Active Listening

Active listening is a communication technique that involves fully focusing, understanding, responding to, and remembering what the speaker is saying. It’s a critical skill in both personal and professional contexts to ensure effective communication and understanding.

This Active Listening Framework comes from Julian Treasure:

🧠𝗥𝗔𝗦𝗔

- 𝗥eceive

- 𝗔ppreciate

- 𝗦ummarize

- Ask

Receive

Objective: Fully take in what the speaker is saying

💡Focus Attention – remove distractions

💡Listening Posture – make eye contact

𝗔𝗽𝗽𝗿𝗲𝗰𝗶𝗮𝘁𝗲

Objective: Show that you are engaged and value what the speaker is saying.

💡Verbal Acknowledgments: “Yes,” “Go on”

💡Non-Verbal Cues: Nodding, facial expressions to demonstrate engagement.

𝗦𝘂𝗺𝗺𝗮𝗿𝗶𝘇𝗲

Objective: Confirm understanding by summarizing what the speaker has said.

💡Paraphrasing: Restate the main point in your own words to ensure clarity.

💡Reflecting: Reflect back any emotional undertones.

For example, “It seems like this issue is causing a lot of frustration for you.”

𝗔𝘀𝗸

Objective: Ask questions to deepen understanding and encourage further discussion.

💡Open-Ended Questions: “Can you explain more about why you feel this way?”

💡Clarifying Questions: “What do you mean by ‘unrealistic expectations’?”

Follow-Up: “Can you give an example of when this approach has failed in the past?”

📚Today’s Story: Richard Feynman’s model of counting

Richard Feynman won the 1965 Nobel Prize in Physics. He was a constant tinkerer and experimenter.

He got interested in how people picture the world and started running experiments.

The results explain the challenges of communication, and tie in the importance of Active Listening.

It started with an interest in how people perceive time.

Feynman best described this experiment to his friend Ralph Leighton which is transcribed here.

He is also on YouTube, telling the story here starting at timestamp 56:41.

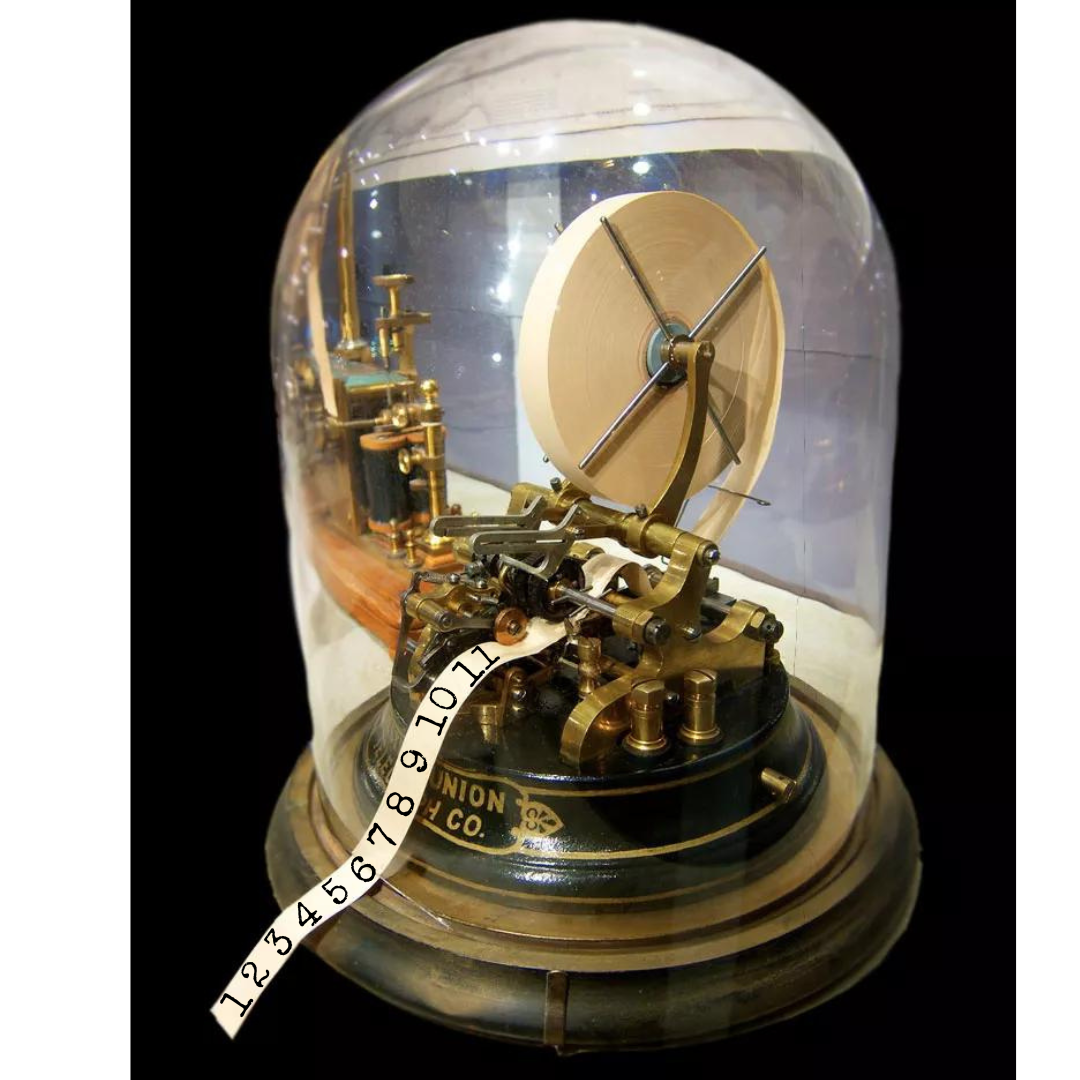

He started counting to a minute without looking at a clock. He found when he counted to 60, only 47 seconds had elapsed quite consistently.

But he couldn’t determine how long a minute was if he didn’t count. He needed to could to track time passing reliably.

Then he started experimenting with counting in different scenarios to see if his perception of time changed.

He ran up and down stairs while counting to 60, but the actual time elapsed did not move from his calibration point. He laid on his bed while his heart rate slowed while counting to 60, but still about 47 or 48 seconds would pass. His perception of time or the speed at which he counted did not seem to be related to his heart rate.

He found he could read while counting. He could type while counting.

But he could not talk out loud while counting.

He described this to Princeton colleague, mathematician John Tukey. Tukey though no way could Feynman read, and that it was crazy he couldn’t count.

They placed a wager. A random book was selected. Feynman read while he counted. When he hit 60 he called “time”. Sure enough, 48 seconds had passed. And he explained what he read.

Tukey’s counting to 60 was calibrated at 52 seconds. He sang “Mary had a little lamb” and spoke out loud and landed on his normal time.

They compared notes.

Tukey imagined a long tape of paper with numbers on it which indexed as he counted to himself. He’s looking at something in his mind which is why he can’t read at the same time.

Feynman is imagining himself talking in his mind when he counts. Because he’s talking in his head, he cannot also talk out loud while counting to himself.

Richard Feynman’s Method:

Feynman could count internally up to 48, which he calibrated to be one minute.

While counting, he could read and get an idea of what he was reading, but he couldn’t speak because his counting process involved an internal dialogue (“one, two, three” in his head).

John Tukey’s Method:

Tukey could count to his calibrated 52 seconds (equivalent to one minute for him) while speaking without any difficulty.

Tukey couldn’t read while counting because his method of counting involved visualizing a tape with numbers changing, which is an optical process.

Key Discovery:

Feynman and Tukey discovered that their mental processes for counting were fundamentally different: Feynman’s was auditory/verbal, while Tukey’s was visual.

This difference explained why Tukey could speak while counting (since speaking didn’t interfere with his visual counting method) and why Feynman could read while counting (since reading didn’t interfere with his auditory/verbal counting method).

This is why it takes ACTIVE effort to get a picture from one person’s head into yours. Practice active listening!

📕1 Book, 🎧 1 Podcast, 📺1 Video, 📰1 Article

Here’s the best stuff I’ve found while researching this.

📕 Today’s Book

Charles Duhigg believes there are three conversation types: either we are trying to make a decision, communicate emotion, or describe identity. Miscommunication happens when on person is trying to communicate emotion and another is trying to make a decision. By recognizing the conversation type we are in, we can get aligned on the other’s intent. Read Duhigg’s 2024 book Supercommunicators. Please buy in your local bookstore. They won’t survive without you.

🎧Today’s Podcast:

Stanford Graduate School of Business has an entire podcast devoted to communication. You can find Charles Duhigg discussing Supercommunicators on Episode 133 (Apple Podcast link). (37 minutes) Julian Treasure discusses his RASA framework on Episode 114 (Apple Podcast link) (28 minutes)

📺Today’s Video:

Harvard Business Review author Amy Gallo helps us understand we each have a default listening mode – Task-oriented, Analytical, Relational, or Critical. We need to intentionally switch from default to the mode the conversation requires. Watch on YouTube here. (8 minutes)

📰Today’s Article:

The US Army describes the importance of Active Listening. This article starts off with a quote from Dumb and Dumber and moves quickly into Army Doctrine. Read in https://www.moore.army.mil/armor/earmor/content/issues/2012/nov_dec/articles/cummings_nd12.pdf

3 thoughts on “A Framework for Active Listening”