Bill Gates believed in his individual talents over a team……until this happened.

As a teenager, Gates thought genius was enough. He wrote entire systems alone — from a class scheduler at 16 to a traffic startup.

But he took some time off in High School to work on the Northwest power grid at a company called TRW. It was his first experience working on a large system with a team and his code came back covered in blue ink.

The reviewer? John Norton, a NASA engineer whose last project, Mariner 1, was destroyed minutes after launch by a missing hyphen in code he oversaw.

Gates’s reaction: ‘Oh wow, this guy is so right.’”

That critique was a turning point. Gates realized brilliance alone had limits — and began chasing not solo perfection, but team perfection.

As he later said: ‘At first I wrote all the code… then eventually there was code I didn’t look at or people I didn’t hire.’

‘At first I wrote all the code… then eventually there was code I didn’t look at or people I didn’t hire.’ – Bill Gates

And here’s why it matters: Gates made the same shift every new manager must make – from doing to delegating; from fixing to feedback. A shift to leading.

I’ll show you the exact turning points from Gates’s memoir Source Code — and how they map to the leadership shift you need to make: from doing everything yourself… to building teams that achieve far more together.

The Solo Genius

It was 1968. Gates was a 13-year-old student at Lakeside High School in North Seattle. An enterprising teacher named Bill Dougall took a computing class and thought he should get computer access at the school. Computers were mostly in universities and government projects then, not in homes. The access they built at the school was remote on an early version of the internet. The students typed on a Teletype ASR-33, which was rented with funds from a rummage sale run by the Lakeside Mother’s Club.

The young Gates started learning how to code. And he got so good he got his first gig that same year — he built his school’s class scheduling system over a summer. It was a difficult project and almost didn’t work. But they figured it out and got hired again to improve the first iteration.

He and his friend Paul Allen soon got access to a million-dollar computer called a PDP-10 at the Computer Center Corporation in downtown Seattle, where they were paid to find bugs in software. This experience with the PDP-10 would be essential to their eventual founding of Microsoft.

Then Bill started his first company.

▶️ This Topic is Also on YouTube

Watch the full episode with visuals and storytelling.

Traf-O-Data

Have you ever seen rubber tubes running across the road? When a wheel runs over them, it creates a puff of air at the end of that hose which is used to count cars. Today, those tubes send data straight into computers. But back in the early 1970s, they punched holes into paper tape. It worked, but the problem was turning that paper tape back into man-readable data — a tedious, manual process.

When Gates was 17, he co-founded Traf-O-Data with Paul Allen and an electrical engineering student at the University of Washington named Paul Gilbert. Together they built a machine that could read those paper tapes and automatically translate them into reports, saving engineers countless hours. And it worked, sort of.

But when the representatives from King County came to see the machine, it broke. Hardware is hard.

Then Bill got his real first taste of a complex system when he took some time off his senior year in high school to work for TRW building a computer system for the Northwest Power Grid.

Not yet 18, he was amazed by what he saw when he first got to the job site. It was a futuristic scene, filled with PDP-10s — he compared it to the control room from his favorite TV show called Time Tunnel. “A wall-sized screen tracked the state of the power grid and every dam and power facility in the Northwest. There were rows and rows of computer terminals… with color graphic screens!”

This project would automate the balancing of power supply from hydroelectric dams and coal power plants, and the fluctuating demand of millions of homes. And they were only allowed 5.26 minutes of downtime per year. “Nothing I had ever worked on required such near perfection. I thought they were joking.”

Nothing I had ever worked on required such near perfection. I thought they were joking. – Bill Gates, gets his first taste of a high consequence system

Up until that point, Gates thought invention was the work of a lone genius — and he was that genius. But now he was part of a huge team and the margin for error was very slim. And here he met John Norton.

Harsh Feedback

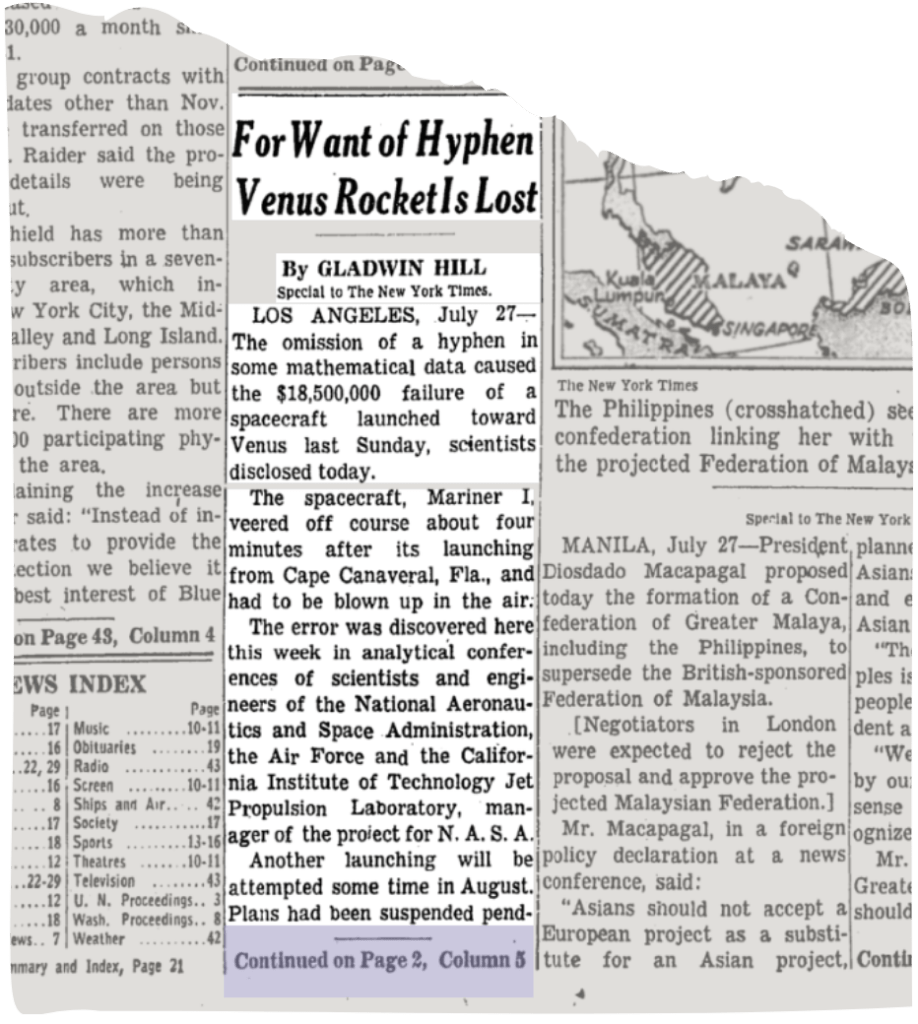

Norton was an engineer twice his age, already marked by one of NASA’s most painful failures. He had worked on a spacecraft called Mariner 1. Mariner 1 was to travel to Venus and record data about its atmosphere. But just minutes after launch, NASA engineers had to press the self-destruct button because of errors in its guidance system.

An $18M spacecraft was destroyed.

The cause of the guidance system failure? A missing hyphen in some software code. Software John Norton had supervised.

Norton carried a newspaper clipping of the failure in his wallet — neatly folded like origami — a constant reminder of accountability. And he had steeled this resolve into writing perfect code on high-complexity, high-consequence systems like this power grid project.

One morning, Gates came into TRW to find a printout of code he had written on his desk. And it was covered in blue ink. His code had been completely torn apart by Norton. Norton gave feedback on the entire structure of the code. Gates read these comments and thought, “Oh wow, this guy is so right.”

When Norton critiqued Gates’s work on the grid project, it stung. For the first time, Gates realized that his brilliance had limits. But he noticed this rigorous feedback and accountability could push him further than he could go on his own. And he began to shift — from putting himself at the center to putting the work at the center. And he asked, “What does perfect software look like anyhow?”

“What does perfect software look like anyhow?” – Bill Gates started to take himself out if the center of this thinking, and put the work at the center.

Harvard Reality Check

At Harvard, the myth of the lone genius cracked further. Gates had been one of the smartest kids in his hometown, but a big fish in a small pond. Here at Harvard that was the biography of every single student. Each was the best person at math they had ever met. Now, they were all in the same lecture hall, struggling in Math 55 together. There was so much more to learn than any of them had ever anticipated.

Gates wasn’t the standout anymore. And if pure brilliance didn’t separate him from the pack, something else would have to.

Paul Allen followed Gates to Boston to work at Honeywell. Paul devoured computer magazines. He was always reading Popular Electronics or Datamation, studying spec sheets for various computers and parts.

They would nerd out about these things and noticed a theme — the microprocessor was becoming more accessible. They were aware of Moore’s Law, which stated the number of transistors on a chip would double every year. Computers were getting more powerful on an exponential curve. They wanted in.

They first thought they should build a computer themselves, but they had built one with Traf-O-Data and it was incredibly complex. It took capital. It took space. It took people to assemble. And when they invited potential clients to look at the Traf-O-Data computer, it broke.

So they focused their ideas on software. “No wire, no factories. Writing software was just brainpower and time.”

They had used an Intel 8008 in their Traf-O-Data computer. They understood how to work with it. And when the Intel 8080 came out, they were jazzed by the specs. Bill told Paul to keep an eye out for someone to develop a computer with an 8080 in it.

Paul called him three months later to tell him about the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics introducing the Altair 8800.

The Altair 8800

The Altair 8800 was missing a few things we take for granted today — most notably, a keyboard, a screen, and any software.

The only way to talk to it was through 25 toggle switches on the front panel and to listen was through 36 LEDs. Just to get the answer to 2 + 2, a programmer had to understand the commands, convert it into binary, and load five lines of code by flipping switches dozens of times. And even then, reading the answer required the user to understand binary — a 4 in binary looks like 00000100, and so there would just be LEDs giving the answer in binary code.

But it could do the math. Here was the opportunity.

Gates and Allen had a vision to put a computer on every desk in every home. In order to do that, they had to make it more accessible.

Bill and Paul learned to program using an accessible language developed at Dartmouth College in 1964 called BASIC. BASIC allowed programmers to type English-like commands, and those commands were converted into the machine language the computer spoke. That conversion process is what’s called an interpreter.

Think of it like this: when you raise your arm, your brain sends electrical pulses down your spinal cord to your muscles, causing them to contract. That is machine code. But if someone asks you to raise your arm, they do it in a spoken language such as English, French, or Chinese. You hear the words, your brain translates them into electrical pulses, and your arm moves.

The spoken language is like BASIC. The electrical pulses are like machine language. And your brain doing the translation is the interpreter.

Each processor spoke its own machine language. A BASIC interpreter for one computer would not work on another, just like an app for an iPhone will not run on an Android. Each platform needs its own version.

They made a bet that the Altair 8800 would take off, and they decided they should build an interpreter they would call Altair BASIC.

But first they called MITS, the maker of the Altair, and told the president, Ed Roberts, they already had a BASIC for the Altair. Ed told them he had received many such calls and the first to build it would get the order.

And so they were off to the races. And they did so without ever touching an Altair themselves. (As it turns out, both parties were hedging their bets. Gates and Allen had not yet built Altair BASIC, though they said they had. And MITS had not yet built a fully working Altair 8800, though it was on the cover of Popular Electronics.)

In the Traf-O-Data days, Paul had figured out how to program a $500,000 computer called a PDP-10 to pretend it was the $360 Intel 8008 processor they used in their system.

So Paul studied the manuals for the Altair and its new Intel 8080 microprocessor, and created an emulator on a PDP-10 at Harvard’s Aiken Lab. And Bill started writing the code for Altair BASIC.

A new teammate: Monte Davidoff

Gates and Allen would discuss their work openly in the lab, in the cafeteria, wherever they were. One day, they were discussing the importance of handling floating-point math — big numbers need to be handled in a certain way. They needed to be first to have a BASIC interpreter for the Altair — this was a race! But they were worried the floating-point math would be tedious and time-consuming. Without it, a popular game like the Lunar Lander they learned to code at Lakeside would never work.

Another student at the table, a freshman math major from Wisconsin named Monte Davidoff, spoke up. “I’ve done that.” Gates quizzed him for hours and, convinced and enthralled, brought him aboard.

As Gates later admitted in Source Code: “My view at the time was that advances in the world sprang from individuals. I pictured the proverbial lone genius, the solo scientist working tirelessly in their field, pushing themselves until they had a breakthrough… My solo-scientist view of the world was grist for an on-and-off debate with Paul. He saw the world advancing through collaboration, in which teams of smart people pulled together toward a common goal. Where I saw Einstein as the model, he saw the Manhattan Project. Both views were simplistic, though in time his would define both of our futures.”

My view at the time was that advances in the world sprang from individuals… Paul saw the world advancing through collaboration, in which teams of smart people pulled together toward a common goal.

Where I saw Einstein as the model, he saw the Manhattan Project.

Both views were simplistic, though in time his would define both of our futures.”

Gates, Allen, and Davidoff worked on BASIC on the PDP-10 in Harvard’s Aiken Lab every night for six weeks. Finally, BASIC was running well enough to demo to MITS. Gates printed the code on paper tape, and handed it to Allen.

Paul Allen flew to Albuquerque. He realized they had forgotten a bootstrap loader telling the Altair to load BASIC into memory. So Paul wrote that on the plane, pencil and paper.

MITS greeted him with an Altair 8800, the first he had ever seen. Paul programmed his bootstrap loader into the machine using the switches on the front panel, which took about 20 minutes. Then he loaded BASIC into the machine with the tape reader, which took about seven minutes.

And Paul typed “PRINT 2+2,” and the machine replied “4,” then “OK.”

“With that, the first piece of software written for the personal computer came to life.”

Ed Roberts, MITS president, exclaimed, “Oh my God, it printed four!” He was as surprised and pleased as Allen.

Bill Yates, MITS lead engineer, handed Allen a now-classic book called “101 BASIC Computer Games,” and Paul entered a version of Lunar Lander. It worked perfectly, demonstrating Monte’s floating-point module.

The product that put Microsoft on the map didn’t come from Gates alone. It came from collaboration. Allen built the emulator, Davidoff the floating-point math. Without this, Altair BASIC would not have happened.

Allen’s model of a team collaborating beat Gates’s model of a lone genius.

Microsoft’s Turning Point

From there, Microsoft scaled quickly. In 1977, when Gates was just 22 years old, they landed the jobs for the BASIC interpreter for the RadioShack TRS-80, the Commodore PET 2001, and the Apple II.

I was surprised to see Apple in the list! When Gates first called Steve Jobs, Jobs replied they already had a BASIC, written by Steve Wozniak. But Wozniak’s BASIC didn’t have a floating-point module. So it was Monte Davidoff’s contribution that sealed the deal with Apple. Those three computer models, led by the Apple II, would go on to sell millions of machines.

In 1986, Microsoft went public. And by the year 2000, the company had grown so explosively that an estimated 10,000 employees had become millionaires through stock options.

Think about that. Ten thousand millionaires. And in 2000, they had 39,000 employees. That kind of scale doesn’t come from one man coding alone. It comes from building a massive team of teams, each united around a common purpose.

Reflection

Years later, Gates admitted on Dax Shepard’s podcast that he once believed in the lone genius myth. But experience taught him otherwise: innovation requires teams.

Dax Shepard: “I have to imagine, for me as a control freak, the very hardest thing that you must have had to eventually do is learn to delegate. Was that one of the bigger challenges for you in Microsoft?”

Bill Gates: “Yeah, and that kind of scaling is a huge challenge. At first I wrote all the code. Then I hired all the people who wrote the code, and I looked at the code. Then eventually there was code that I didn’t look at or people that I didn’t hire. And of course the average quality per person is kind of going down, but the ability to have big impact is going up.

That idea that a large company is imperfect in many ways and yet it’s the way to get out to the entire world and bring in all these mix of skills — most people don’t make that transition. And there are times where you go, oh my God, I just want to write the code myself. The famous thing I’d always say is, you know, I could have come in and written that over the weekend. Well, eventually I couldn’t.

The individual contributor and the orchestrating of an organization aren’t often found together, because there’s a certain contradiction to that craftsman.”

The shift was complete. The boy who thought he could do it all alone became the leader who built an empire of teams — a company of 228,000 people today.

Gates himself admitted it: the hardest shift he ever made was moving from being a craftsman who could do everything himself… to orchestrating an organization that could reach the world.

That’s the same shift every new leader must make.

Closing Lesson

Bill Gates’s story mirrors the arc every new leader faces. We start by relying on our own skills — because that’s what got us here. But the real shift is moving from solo brilliance… to building and trusting teams.

Because solo brilliance sparks invention. Teams sustain it.

So let me ask you: when was your humbling moment — the one that showed you you couldn’t do it alone?

And if you want more leadership lessons told through real stories, hit subscribe — I’ve got more coming soon.