I believe emotional intelligence is mislabeled as a “soft skill.” It sounds too much like “sensitivity” or “agreeableness,” but a display of emotional intelligence is actually tough as nails.

In high-stakes environments, boardrooms and battlefields alike, emotional intelligence isn’t about being nice. It’s about knowing the role of emotions in decision making, and using that knowledge to make better decisions, big and small. It’s about staying calm when panic is contagious, to think when thinking is hardest, and choosing wisely.

To illustrate my point, I’m going to tell the story of emotional Intelligence saving 220 million people from nuclear annihilation in 1960.

I. The Ballistic Missile Early Warning System in Thule, Greenland

In 1960, deep inside the Arctic chill of Thule, Greenland, the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS) had just been commissioned to give the United States a whopping 15 minutes advanced notice of a nuclear attack from the Soviet Union.

Fifteen minutes. Just enough time for a counter strike.

Mutually assured destruction.

And on October 5, 1960, this new system indicated hundreds of Soviet nuclear missiles were headed toward the United States. It looked like a scene from the 1983 film Wargames.

The U.S. counter strike, called the Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP), was set to launch over 3,000 nuclear weapons at nearly 4,000 targets within the Soviet Union, many of them cities. The SIOP was designed to be irreversible once initiated. Once the order was given, SIOP could not be slowed, and it could not be stopped. If followed, it would have killed 220 million people in three days.

But one man didn’t panic. Air Marshal C. Roy Slemon, the vice commander of NORAD.

Operating a system designed to give just 15 minutes of warning to enable a counterstrike, and in the very high-pressure scenario it was deployed to detect-where many would panic, Slemon paused. He asked one simple question, and made a critical decision. That moment wasn’t guided by physical strength or aggression – but was tough as nails. That moment guided by was emotional intelligence.

But to really understand the weight of Slemon’s decision—and why emotional intelligence made the difference—we need to rewind. How did the world get to the brink of catastrophe? And more importantly: what can a decision made in a nuclear command center teach us about how to lead under pressure in our own lives and work?

II. Fear, Power, and the Birth of The Bomb

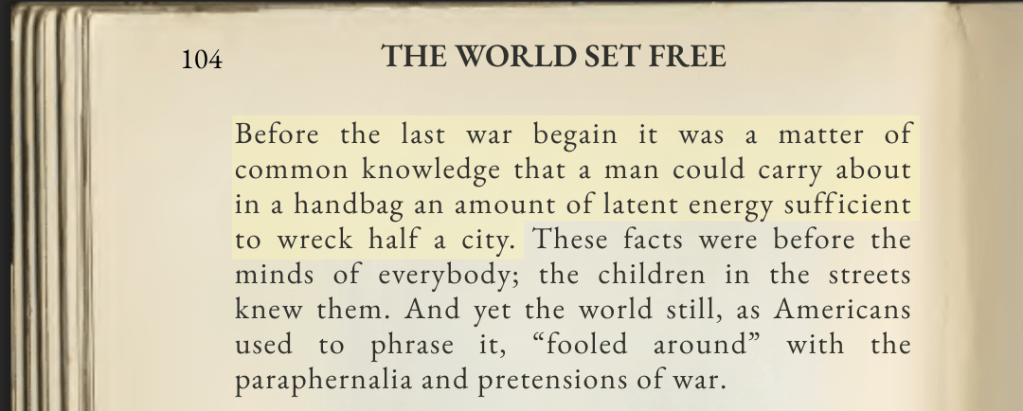

The atomic bomb was a vision of destruction that began in fiction. Science fiction legend H.G. Wells imagined a bomb that could fit in a handbag and flatten a city in a book he wrote in 1916 called The World Set Free.

Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard read this book and met with Wells himself many times to discuss. Seventeen years later, while crossing the street in London in September 1933, Szilard had a vision of a nuclear chain reaction – the physics of how such a weapon might work.

Prompted by James Chadwick’s recent discovery of the neutron, Szilard began to think differently about atomic structure. He realized that if a molecule consistently emitted more than one neutron after absorbing just one, those extra neutrons could go on to split other molecules—releasing even more neutrons in the process. This could set off a self-sustaining chain reaction, growing exponentially with each cycle. In theory, it would release an enormous amount of energy almost instantly.

And if that kind of reaction was possible, then so was a bomb—one just like H.G. Wells had imagined, but unlike anything the world had ever seen.

His concern deepened as he reviewed scientific papers coming out of Nazi Germany—papers that suggested German physicists were asking the same questions and making troubling progress on the answers. Having fled the fascist regime himself, Szilard believed that if Hitler could build a nuclear bomb, he would not hesitate to use it.

Szilard visited Albert Einstein at his home on Long Island in 1939. Einstein was largely retired at this time, and Szilard caught him up on the state of physics. When Szilard described the possibility of an Atomic Bomb, Einstein replied, “I did not even think about that.”

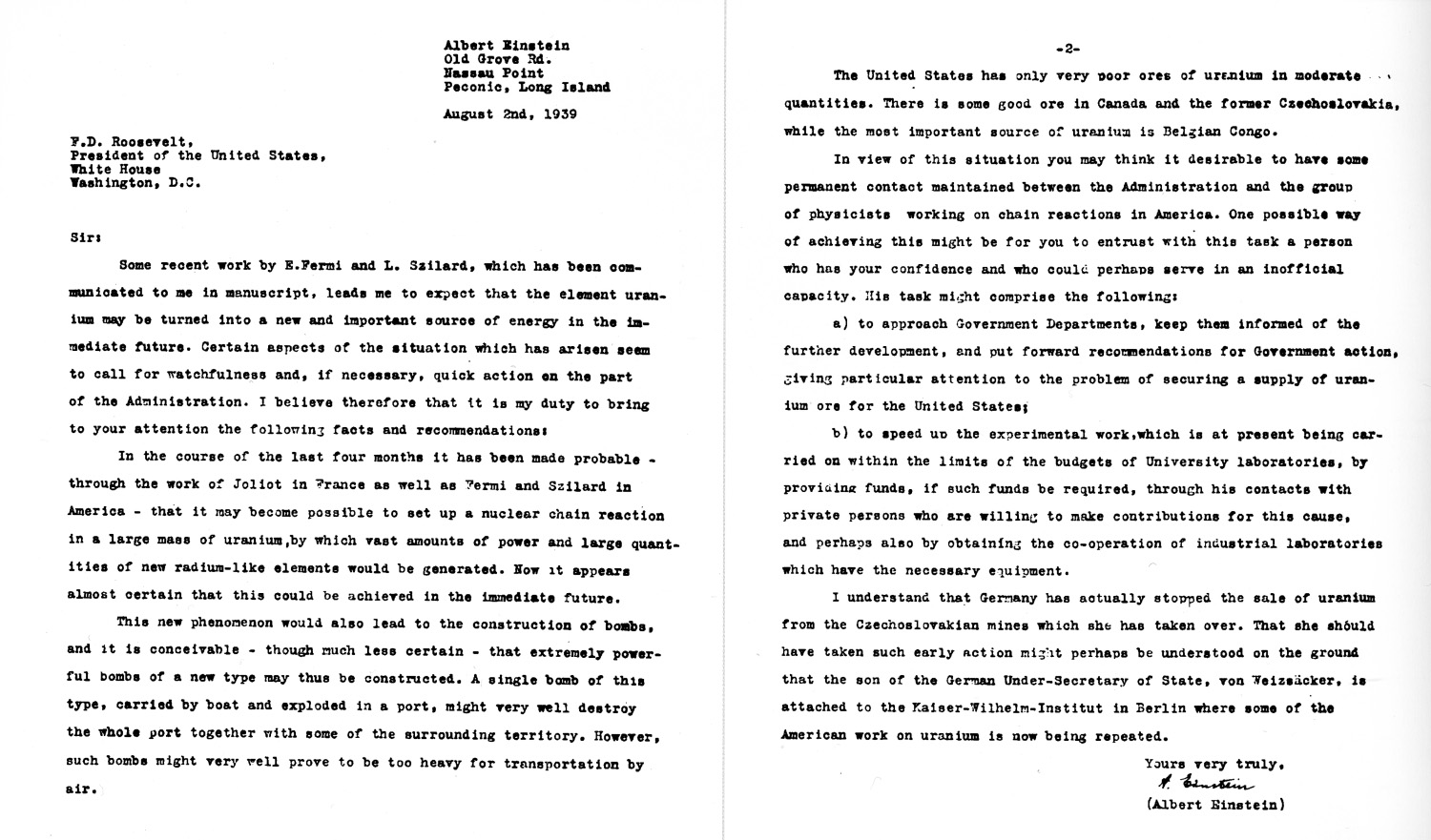

The two men co-authored a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, delivered on August 2, 1939, warning that Hitler was working on “extremely powerful bombs of a new type” and urging the U.S. to centralize Uranium research through the cooperation of national industrial laboratories. They also cited Germany had stopped selling Uranium from Czechoslovakia which Hitler had recently occupied as a sign that the Nazi government was hoarding nuclear material for their own bomb.

Just weeks later, on September 1, 1939 Hitler had invaded Poland. FDR wrote back on October 19, 1939 thanking Einstein for the letter which he had taken so seriously as to commission a study of Uranium.

Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941, pulling the U.S. into WWII. And by 1942, the Manhattan Project was born.

180,000 people worked on the Manhattan Project and three years later, in July 1945, the first nuclear core was assembled.

H. G. Wells imagined an explosive the size of suitcase. This first nuclear core was actually the size of tennis-ball and weighed as much as a bowling ball. And when it was tested on July 16, 1945, it made the New Mexico desert hotter than the surface of the sun and turned the sand to green glass.

The weapon was dropped on the Japanese cities Hiroshima and Nagasaki killing nearly 250,000 people. Almost all those killed were civilians. Japan announced its surrender 6 days later ending World War 2.

But the nuclear genie was out of the bottle.

Not long after, several members of the Manhattan Project—among them Klaus Fuchs and Oscar Seborer—were exposed as Soviet spies. The USSR, now armed with stolen knowledge which took years off their nuclear weapon development program, successfully tested its first atomic bomb in 1949.

The Cold War had begun.

What began as a scientific theory—and a race against Hitler—had reshaped global reality. The bomb was no longer an idea. It was a fact. And in its aftermath, a new kind of fear settled over the world.

For the first time in history, total annihilation could happen in minutes. And everyone—citizens, children, presidents—was expected to live with that knowledge.

III. Living Under the Bomb

The Cold War redefined what it meant to feel safe.

School children were taught to duck-and-cover under their desks by Bert the Turtle, a cartoon funded by the U.S. Federal Civil Defense Administration. Families built backyard fallout shelters. Cities tested air raid sirens.

The 1953 short “Duck and Cover” taught school children to hide under their desks to protect themselves from a nuclear attack. I find the discarded flower telling – it’s the loss of innocence and a carefree childhood. This level of fear was brand new.

The 1957 Soviet launch of Sputnik, the first human-made object to orbit Earth, was fitted with a short-wave radio which broadcast a “Beep” anyone could dial in to. A thrilling an in 1957 shocked America, confirming that the USSR had a technological edge. Panic set in as fears of a “missile gap” took hold.

In response, U.S. bombers were placed on 24-hour alert. Deterrence became the doctrine: prevent a first strike by guaranteeing mutual destruction. This policy, known as Deterrence Theory, remains active to this day.

IV. Thule, Greenland and the Plan for Armageddon

On October 1, 1960, a new line of defense quietly came online at the edge of the Arctic Circle.

Buried in the frozen terrain of Thule, Greenland, the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System—BMEWS—began scanning the skies. With a 3,000-mile detection range, it was designed to do one thing: spot incoming Soviet missiles as they arced over the North Pole toward the United States.

It gave the U.S. just fifteen minutes to respond.

Fifteen minutes to detect, decide, and launch a counterstrike before American cities disappeared in fire.

The response plan was already in place. It was called the Single Integrated Operational Plan—SIOP. Once activated, it would unleash over 3,000 nuclear warheads on nearly 4,000 Soviet targets. Eighty percent of the targets were military, 20% were civilian. (Schlosser page 215) It would kill 220 million people in 3 days. And once the SIOP was started, there was no way to slow or stop it. It was intentionally irreversible.

“The SIOP required only that a Go code be transmitted, and after that, nothing needed to be said—because nothing could be done to change or halt the execution of the war plan.” | —Eric Schlosser, Command and Control, p. 261

It was the logic of deterrence made real.

A system built on speed, certainty, and total destruction.

Just four days after BMEWS came online, it lit up with what looked like a full-scale Soviet launch.

The countdown to the end of the world had begun.

V. The Moment of Clarity: Emotional Intelligence in Action

Inside NORAD, alarms were blaring. The radar data was clear: a massive Soviet strike was underway. The system was doing exactly what it was built to do—detect, escalate, and trigger a response.

Air Marshal C. Roy Slemon, the Canadian vice commander of NORAD, was briefed. The readings showed hundreds of missiles in the air. The logic of the SIOP dictated immediate retaliation. Every second mattered.

But Slemon didn’t rush. He didn’t panic. In fact, he paused.

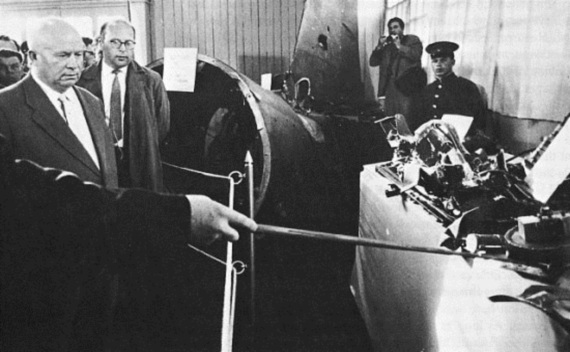

He asked a simple question: “Where is Khrushchev?”

Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet premier, was known to be shrewd and theatrical. Just months earlier, the Soviets shot down a U-2 spy plane piloted by Francis Gary Powers. The U.S. presumed the pilot dead and published a cover story. But Khrushchev masterfully exposed the U.S. government’s cover story as a lie. He allowed American officials to repeat the cover story several times—that it was a weather plane, that the pilot worked for NASA, that it had launched from Turkey—before revealing that Powers was alive, flying for the CIA, and had taken off from Pakistan.

And Slemon knew Khrushchev would have been the center of this decision to launch. And he knew the U.S. would have an idea of where he was.

Rather than launching SIOP, he paused. And then he asked “Where the hell is Khrushchev?”

The answer: Khrushchev was in New York City. At the United Nations.

“Well, gentlemen,” Slemon said. “Let’s just sit back and enjoy the show, because we’re not at war.” – Roy Slemon upon learning the Soviet Premier was in New York City.

Slemon knew the Soviets would never launch a first strike with their leader in the target zone.

Twenty agonizing minutes passed. No missiles landed. Eventually, the source was discovered: the radar system had picked up the rising moon over Norway, misinterpreted as incoming warheads.

The world had come within minutes of nuclear war.

And it didn’t stop because of better technology or quicker reflexes.

It stopped because one person stayed calm enough to think clearly.

That is emotional intelligence.

Not warmth. Not people-pleasing. Not passivity.

Clarity under pressure. Control in chaos. Insight when fear clouds everything.

VI. Emotion vs. Perception

The word emotion literally means “to move.” You can see it in the root: motion. An e-motion is a biological impulse—a push to act without thinking.

And when emotions are in control, they distort how we see the world.

Psychologist Paul Ekman put it this way:

“We cannot perceive anything in the external world that is inconsistent with the emotion we are feeling. We cannot access the knowledge we have that would disconfirm the emotion we are in.”

Fear makes us find more reasons to be afraid. Anger justifies more anger. Even joy can blind us. When we’re emotional, we don’t see reality—we see through a lens that reinforces whatever we’re already feeling.

Take Peloton, for example. As I detailed in my case study, during their meteoric rise, they were euphoric—too euphoric to make clear-headed decisions. That unchecked excitement led to overreach, misjudged investments, and ultimately, a crash. They were buried by decisions made in a good mood.

Back in the Cold War, the emotion was fear—global, unrelenting fear. Slemon was operating a system that gave just fifteen minutes of warning before potential annihilation. Time pressure. Existential threat. Total uncertainty.

And yet, he stayed calm. He thought clearly.

That’s the presence of mind that emotional intelligence makes possible.

It’s not about suppressing emotion. It’s about creating space—space between the feeling and the action. Space to think. Space to choose.

Because when we act while gripped by emotion, we often fail.

That’s the point: emotional intelligence gives us the space to choose—to act from clarity, not impulse.

And it’s not just a vague idea or a personality trait.

It’s a skillset. A discipline. A framework.

One you can learn. One you can practice. Especially when the pressure is on.

Let’s break it down.

VII. Emotional Intelligence Is a Skill—And Here’s How to Build It

Air Marshal Slemon didn’t get lucky. He didn’t make a gut decision and hope for the best. He practiced the toughest form of leadership: staying clear-headed when fear takes over the room.

What he demonstrated wasn’t instinct. It was emotional intelligence in action—and it wasn’t accidental.

Psychologist Daniel Goleman popularized emotional intelligence not as a personality trait, but as a set of trainable competencies. In moments like Slemon’s, each one of them is at work. Here’s how they looked, and how they apply to you.

1. Self-awareness

Recognize your emotions and their effect on your thinking.

Slemon understood the moment’s gravity—but he didn’t confuse adrenaline with truth. He noticed his fear, but didn’t let it shape his thinking. Self-awareness begins with the ability to name what you’re feeling without being ruled by it.

✅ Try this: Pause in tense moments and ask, “What am I feeling right now—and how might it be distorting my judgment?” I was surprised by how helpful emotional definitions are. Get my list here.

2. Self-regulation

Manage your emotions, stay in control, and choose your response.

Despite immense pressure, Slemon didn’t lash out or rush. He waited. He asked a grounded question. He gave space for facts to emerge. That’s the essence of self-regulation: action with intention.

✅ Try this: Build a pause into your decision-making—especially when emotions are high. Ask yourself: “What’s the cost of acting too soon?”

3. Motivation

Channel your emotions into purpose-driven focus.

Slemon wasn’t paralyzed by fear—he was driven by a deeper motive: avoid catastrophe. Motivation in EQ isn’t about ambition; it’s about staying anchored to purpose when emotion tempts you to veer off course.

✅ Try this: Reconnect with your core goal before acting. Ask, “What outcome really matters here?”

4. Empathy

Understand what others feel and see from their perspective.

When Slemon asked, “Where is Khrushchev?” he stepped into his adversary’s shoes. Why would the Soviets attack with their leader in harm’s way? That question cut through the panic. Empathy is often the key to clarity.

✅ Try this: In conflict, ask: “If I were them, what would I be thinking right now?” It often reframes everything.

5. Social Skill

Communicate, influence, and hold calm in group dynamics.

Slemon held the room. He didn’t just manage his own emotions—he created space for others to think clearly. That’s the social side of EQ: not just staying grounded, but grounding others.

✅ Try this: When tensions rise, model calm aloud. Name uncertainty. Ask focused questions. It de-escalates chaos.

VIII. Conclusion: The Toughest Skill on Earth

Emotional intelligence is not soft. It’s not passive. It’s not optional. It is strategic. It is powerful. And sometimes, it is the only thing that stands between us and catastrophe.

The next time you face pressure, remember: it’s not strength that defines the moment. It’s clarity. It’s calm. It’s choice.

That’s emotional intelligence. And it may be the toughest skill there is.

Want to learn more?

Get my free guide on Emotional Intelligence here.