In her 2015 Harvard Commencement Speech, Natalie Portman shared a revealing moment:

“I felt like there had been some mistake, that I wasn’t smart enough to be in this company, and that every time I opened my mouth I would have to prove that I wasn’t just a dumb actress.”

At just 18, after starring in The Professional and Star Wars: Episode I, Portman somehow doubted her right to be at Harvard.

She is a movie start. But she feels like she doesn’t belong.

That’s called imposter syndrome — and I’ve been there.

I didn’t fully understand it until I learned about the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

Learning about Dunning-Kruger helped me recognize what I was feeling — and what to do next.

Hilariously, this story begins with a remarkably inept bank robber who thinks he is exceptionally clever.

A really dumb bank robber thinks he’s really smart

In 1995, a man named McArthur Wheeler walked into a bank in Pittsburgh and robbed them without any attempt at disguising himself. He was quickly arrested, and when the police showed him the footage from the surveillance tapes he muttered “But I wore the juice.”

But I wore the juice? What the heck does that mean?

Pittsburgh police commander Ronald Freement explained:

“Someone told (Wheeler) that if you put lemon juice on your face, it makes you invisible to the security camera.” [1]

It turns out Wheeler knew lemon juice was used in making invisible ink. And he thought it would hide his face from the cameras!!! Remember this – I’m going to introduce a term, “The Peak Of Stupidity,” in a moment. This. Is. It.

Psychologist David Dunning read through a new report about this bank robber. He wondered:

If Wheeler was too stupid to be a bank robber, perhaps he was also too stupid to know that he was too stupid to be a bank robber — that is, his stupidity protected him from an awareness of his own stupidity. [2]

Dunning and a graduate student Justin Kruger set off to study the relationship between confidence and expertise in decision making. They found something quite surprising which they called “The Dunning-Kruger Effect.” And it explains both overconfidence, and underconfidence.

What Is the Dunning-Kruger Effect?

Psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger discovered a paradox:

- People with little experience often overestimate their abilities.

- People with more experience often underestimate their abilities.

Here is the graph from their paper “Unskilled and Unaware” [3]:

In this figure, and 3 other like it, Kruger & Dunning show participants in the bottom quartile thought they were nearly 30 percentile points better than they really were, while top performers underestimated themselves.

It’s like the Bottom Quartile getting an F on a paper they thought they earned a C in. The Upper Quartile thought they got an A-, they actually got an A+.

Why? Because beginners “don’t know what they don’t know,” while experts do.

And self-doubt tends to happen when we think we know it all, and then learn that’s not actually true.

I’ll tell you the story of when this concept was helpful to me. But first I’ll tell you a story when it was important to my niece.

A Crayon Sketch and a Hug

I was talking with one of my nieces, who was in her freshman year of college.

A professor had recognized her potential and encouraged her to tutor his class. But instead of stepping into that opportunity, she dropped the course. She didn’t think she was prepared for the opportunity. She doubted the talent and aptitude he saw in her.

She was the top student.

But she felt like an impostor because she could see how much she still had to learn.

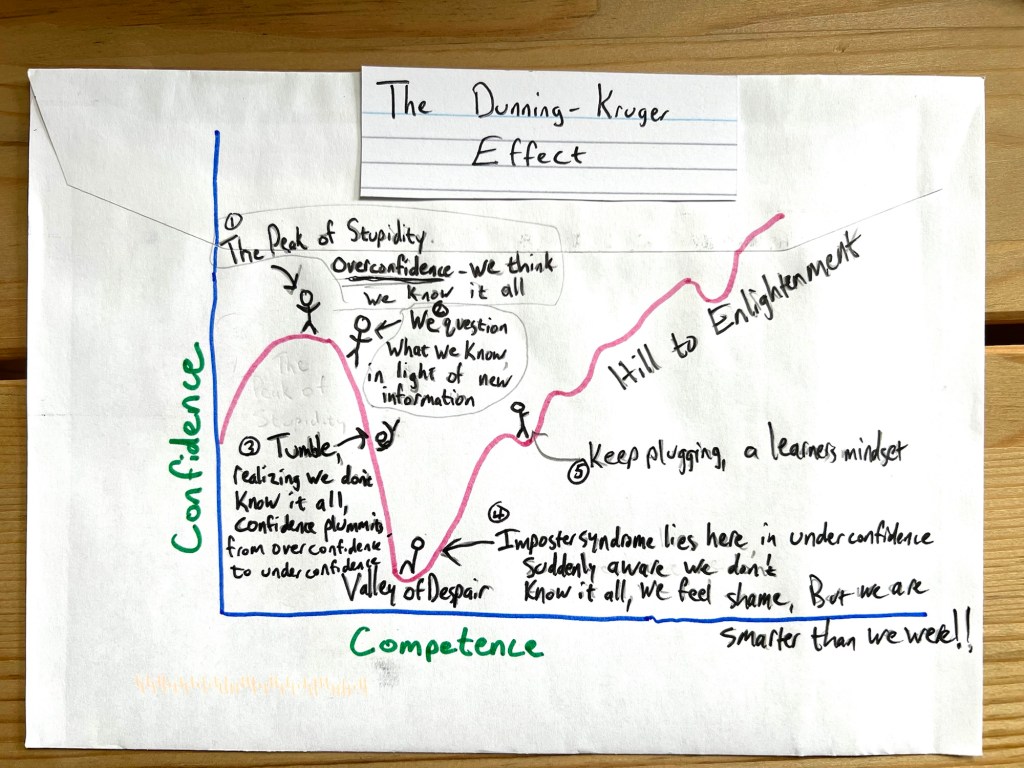

So I grabbed a crayon and an envelope and drew this version of the Dunning-Kruger curve on a napkin:

I explained:

Now here’s the curve.

It shoots up right away. That first peak? That’s called the Peak of Stupidity—funny name, I know. But it’s not about being stupid. It’s that early moment when we think we’ve got it all figured out. Like, “I totally get this. I’m crushing it.” You were probably here a few weeks into class—top of the curve. Aces on the essays, nodding along in discussion. You felt strong.

But now I’m drawing this big drop.

This is where it gets tricky. Something happens—maybe someone asks you to explain what you know, or you’re asked to tutor someone else—and suddenly, all that confidence takes a nosedive.

This is some kind of threshold, something changed and now you think: “Wait, I’m supposed to be the expert? I’m not ready for that!”

This dip is called the Valley of Despair. And this, I think, is where you are now.

It feels like you’re failing or like you’ve been faking it all along. That’s not true, by the way. That feeling is called impostor syndrome. It’s the belief that you don’t deserve the success you’ve earned—that you’re just lucky, or people have overestimated you. But listen: you’re not in the valley because you’re worse than your classmates. You’re in the valley because you’re more aware. And that’s actually a sign of growth.

Now I’m drawing this steady climb.

This is the Hill to Enlightenment. It’s slower, not flashy. It’s built on real understanding. You get there by staying curious, by teaching, by making peace with what you don’t know yet. That’s where confidence comes back—not inflated this time, but earned.

So where are you on this curve?

Right here, in the dip. But that’s not a reason to walk away. It’s a reason to keep going. The people who grow the most are the ones who make it through this part. And the fact that your professor asked you to tutor? That tells me—and should tell you—you’re farther along than you think.

You’re not an impostor. You’re a learner. And you’re doing great.

She hugged me. Then hung that sketch in her dorm room.

You’re here because you’re climbing, too.

From Confidence to Renewed Curiosity: My Daughter’s Lesson

Anyone with kids sees this in children all the time.

When my young daughter learned what a bee was, she thought everything flying was a bee. She thought she knew everything about the world.

This is popularly called “The Peak of Stupidity” – you know just enough to think you know it all. “Enough to be dangerous,” we sometimes say.

Then she learned about a house fly. It looks a lot like a bee, but black. She thinks – “ok, there are 2 different bees, yellow and black. They fly like this. I still know everything about the world.“

But then we went camping and she saw a dragonfly. This dragonfly was long, green, and was hovering, as unlike a bee as could be. And then it flew away from us backwards. She was stunned!

This is when she started to recognize how much there was to learn about the world. This is a tumble off of the “Peak of Stupidity” into the “Valley of Despair.”

But she didn’t get dumber! She got smarter – she learned dragonflies exist. The difference is that she learned there is a lot more to learn about the world.

If you’re searching for “Dunning-Kruger” or “Valley of Despair,” you might feel like you’re slipping too.

But take heart: it’s a sign you’re growing.

It’s a sign you just got smarter.

Why It’s Harder as Adults

Children live in a constant state of wonder. As adults, we start to feel confident in familiar surroundings — at work, in relationships, in daily life.

We are in learning mode for our entire lives and then, suddenly, we leave college. We start working, our learning mindset diminishes.

Then, new challenges arrive: promotions, leadership roles, new responsibilities. As children we’d have shifted into a learning mode. But as adults, sometimes this turns into a shaken confidence.

It hit me hard – I was saying out loud: “I am not the right person for this moment.”

Looking back, I see how well I actually performed — and how much it set me up for future success.

The key? Mindset.

A Learning Mindset

Albert Einstein replied to a letter from a 12-year-old from Washington, DC named Barbara, who said it takes her longer to do her math work than it takes her classmates:

“Do not worry about your difficulties in mathematics; I can assure you that mine are still greater.”

-Albert Einstein. Letter to Barbara. January 7, 1943.

Even Einstein knew what it was like not to know everything. He didn’t doubt himself – he dug in and learned what he didn’t know.

Tom Hanks could resonate with the imposter syndrome a character felt:

“No matter what we’ve done, there comes a point where you think, ‘How did I get here? When are they going to discover that I am, in fact, a fraud and take everything away from me?’”

You’re not alone. Not even close.

📚 My Former Theater Career: I Got Stuck in a Valley of Despair

Before entering the world of leadership and engineering, I had a whole different life in theater.

At 16, I was hired as an apprentice in a summer theater company. It felt like magic. I was utilizing both sides of my brain, solving technical problems and creating something innovative. I worked my way up quickly, and eventually joined the professional theater scene, working with top designers and on major productions. I even toured with a magic show and worked U2 and Dave Matthews Band concerts.

It felt like my true calling. I was learning fast and earning praise. But the freelance nature of the work was brutal. One January, I had no gigs lined up. My cash dried up quickly. I couldn’t afford food. It became clear my skills weren’t yet enough to sustain me. I enrolled in university to study theater.

In college, I was way ahead of most undergrads. I had more professional experience than they had amateur experience. One professor noticed and invited me into a graduate-level scenic design class. It was a rare opportunity. I felt honored—and ready.

But I wasn’t.

I was so used to showing people how good I was. I was not used to learning.

The class included three talented grad students and one more undergrad named David. While I floundered, David kept showing up, learning fast, and pushing through.

I froze. I doubted myself. When my work was critiqued, I made excuses instead of learning.

But that other undergraduate crushed it! David Korins is now a Tony Award-nominated designer whose work you’ve likely seen—Hamilton, Beetlejuice, the Academy Awards. We literally sat next to each other in the same class. But I changed majors. He kept going right to the top of the field. Amazing!

That was my first fall from the “Peak of Stupidity” into the Valley of Despair.

Years later, I would fall into it again as a leader. But this time, I had a name for it. Changing majors felt like failure at the time. But looking back now, it was preparation. When I later found myself in the Valley of Despair as a leader, I had a name—and a framework—to help me navigate it.

What the Dunning-Kruger Effect Really Means

True growth comes when you see how much there is still to learn.

It’s painful, yes. But it’s also the foundation of expertise.

Even Maya Angelou said:

“I’ve written eleven books, but each time I think, ‘Uh oh, they’re going to find me out now.'”

Natalie Portman, Tom Hanks, Wolfgang Puck, Tina Fey — they all fought imposter syndrome.

They weren’t failing. They were growing.

And so are you.

The Climb Out of the Valley

The key is to reframe learning as your job. You don’t have to have all the answers. You just have to stay curious and keep going.

As John Mayer sings in Why Georgia:

“Don’t believe me when I say I’ve got it down.”

Real leadership isn’t about “having it down.” It’s about knowing there’s always more to learn.

If you’re in the Valley of Despair right now, you’re not broken.

You’re not broken — you’re just in the Valley of Despair. It’s not the end. It’s the beginning.

As Teddy Roosevelt wrote in his autobiography:

“Do what you can, with what you’ve got, where you are.”

Progress doesn’t require perfection — just motion.

And there is a path forward.

Continue Growth through Self-Awareness

It’s very hard to understand something without the language. Self-awareness comes in many forms.

I’ve found awareness of my emotional state is crucial, and I created a guide around it.

If you’re navigating the Valley of Despair right now, here are some common questions people ask—and encouragement to help you keep climbing.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Valley of Despair and the Dunning-Kruger Effect

What is the Valley of Despair in the Dunning-Kruger Effect?

The Valley of Despair is a key phase in the Dunning-Kruger Effect where individuals, after an initial burst of confidence, realize how much they don’t know. This paradox happens because beginners overestimate their abilities since they lack the experience to recognize their own limitations. As they gain more knowledge, they start to see the vast complexity of the subject. This realization leads to self-doubt and uncertainty—the Valley of Despair. To move past this phase, individuals must continue learning, embrace challenges, and build true expertise over time.

How do I get out of the Valley of Despair?

To move past the Valley of Despair, first recognize it and don’t get stuck! Next, focus on continuous learning, seek mentorship, and practice your skills over time.

Why do people get stuck in the Dunning-Kruger Effect?

People get stuck due to cognitive bias, lack of self-awareness, and difficulty in receiving feedback that challenges their assumptions.

How do I know if I’m in the Valley of Despair?

If you feel overwhelmed, full of self-doubt, and suddenly question your abilities — especially after gaining more experience — you may be in the Valley of Despair. Ironically, this feeling often signals true growth, not failure.

How can I climb out of the Valley of Despair?

The key to climbing out is reframing discomfort as a sign of learning. Focus on steady improvement, embrace humility, seek feedback, and remind yourself that real expertise comes through persistence. Growth is often invisible before it becomes undeniable.

Is feeling like an imposter normal during learning and leadership growth?

Yes. Even highly successful people like Maya Angelou, Tom Hanks, and Natalie Portman have spoken about struggling with imposter syndrome. Feeling like an imposter is often a sign that you’re pushing yourself into new and necessary levels of growth.

References

[1] Michael A. Fuoco, “Trial & Error,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (Pittsburgh, PA), March 21, 1996, 37. (return to article)

[2] Morris, Errol. “The Anosognosic’s Dilemma: Something’s Wrong but You’ll Never Know What It Is (Part 1).” Opinionator (blog). New York Times. June 20, 2010. https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/06/20/the-anosognosics-dilemma-1/. (return to article)

[3] Kruger, Justin, and David Dunning. “Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77, no. 6 (1999): 1121-34. (return to article)