When most people hear the word process, they think of something rigid — checklists, approvals, bureaucracy.

It feels like the opposite of creativity. Creativity, after all, is supposed to be spontaneous and free.

But the truth is, the best creative breakthroughs hide a process beneath it — a structure that channels imagination into form. The only difference is that creative processes are rarely visible. The mess gets hidden, the iterations are erased, and the final product looks inevitable.

That illusion feeds a dangerous myth: that process kills creativity. In reality, a process should be designed to produce consistent results, and a transparent design process accelerates creativity.

And the idea is four hundred years old.

Galileo Created Transparency

Centuries before anyone used the word innovation, Galileo confronted this same tension between imagination and reality. As biographer Laura Fermi puts it,

“Galileo invented experiments, considered them a necessary regular practice, and came to regard them as the criterion in discriminating between the unlimited possibilities of human imagination and the realities of the physical world.”1

Galileo didn’t just dream; he built a process to test dreams against the world. His experiments made discovery transparent — visible, measurable, and repeatable – a process we now call The Scientific Method.

One famous demonstration involved dropping unequal weights of the same material from the Leaning Tower of Pisa to prove they would strike the ground at the same time. This experiment settled an intellectual debate with observable proof.

In 1971, astronaut David Scott repeated Galileo’s insight on the surface of the moon. He dropped a hammer and a falcon feather simultaneously. They hit the lunar surface together, just as Galileo had predicted.

He showed that creativity without transparency is fantasy, but creativity with transparency becomes science.

We meet our next story in 2005.

The Keyboard Derby — Transparency in a Creative Process

Fifteen engineers from Apple’s User Interface department sat in a conference room called “Between” in October 2005. Across the hall were rooms named “A Rock” and “A Hard Place.” The names were whimsical, but the stakes were serious. Project Purple, Apple’s secret iPhone effort, was in trouble. If the team could not solve one problem, the project would be cancelled.2

Steve Jobs had envisioned a smartphone “without the stupid keyboard.” Physical keys, as he said in the 2007 keynote unveiling the product, were “the problem.” He wanted a touchscreen keyboard that appeared only when needed. The challenge: no one had ever built one that worked.

Henri Lamiraux, Apple’s vice president of iOS Software Engineering, gathered the entire user-interface department and gave a single directive: “Starting from now, you are all keyboard engineers.” From that moment, every other project paused from a UI perspective. The backlog was clear—make typing on glass work.

For an entire month, the team produced nothing but keyboards. Every other day they gathered to show prototypes, test them, and refine ideas. They called it the Keyboard Derby. It was a race of ideas conducted in the open: everyone could see what others had tried, what failed, and what was improving. The rhythm of near-daily demonstrations forced progress and made the work audible. Transparency had become the process.

An engineer named Ken Kocienda would win the race. But only after 6 completely different keyboards, an experience he documented in a wonderful book called Creative Selection.

Julien Dorra, who teaches a tech design history course in Paris, got in touch with Ken on Bluesky to ask him about his experience.

@kocienda.bsky.social Hi! I’m teaching a tech design history class here in Paris where your keyboard is one of the key innovation stories. I’m making the class more hands-on with props, demos. Crazy idea, I want to build a Blob Keyboard simulator 😅 so they can *feel* the design iterations

— Julien Dorra (@juliendorra.com) March 30, 2025 at 9:25 PM

try this

— Ken Kocienda (@kocienda.bsky.social) Mar 30, 2025 at 23:21

[image or embed]

And then Julian created a simulator of the keyboard. Try this – it actually works!

Try the 2005 “Blob Keyboard” prototype. Tap for middle letter; swipe left/right for side letters.

You have probably found that prototype a little tricky to use. Ken did too. But the real value of this early concept was not its performance. It was what he learned from the feedback he received while demonstrating it to his peers.

Some engineers had simply put a QWERTY keyboard on the screen, but the keys were so small that accurate typing was nearly impossible. Ken’s “blob keyboard” explored a different tradeoff. The keys were larger and easier to hit, but each contained multiple letters. Selecting an individual letter required a gesture. The result was accurate tap targets, but a mentally taxing interaction. You had to locate the letters in an unfamiliar arrangement and then remember the gesture to select the right one.

That feedback mattered. It showed Ken that there was value in larger keys, but gesture-based selection was too slow and too cognitively expensive. His eventual solution would return to a traditional QWERTY layout. But to make small keys usable, he would pair them with an entirely new concept: autocorrect.

About a month later, in a conference room at Apple called Between, Ken Kocienda sat beside his boss’s boss, Scott Forstall, in front of an early iPhone prototype called the Wallaby. The device, tethered by a thick cable to a blue and white Apple G3 desktop computer, was essentially a multitouch display connected to a bare logic board.

Forstall spent more than an hour testing fourteen keyboards. Each had the same flaws: the keys were too small or too slow to use accurately.

Ken’s was last. He had demonstrated five or six prior designs for his coworkers, making improvements each time. This was the first demo for Scott.

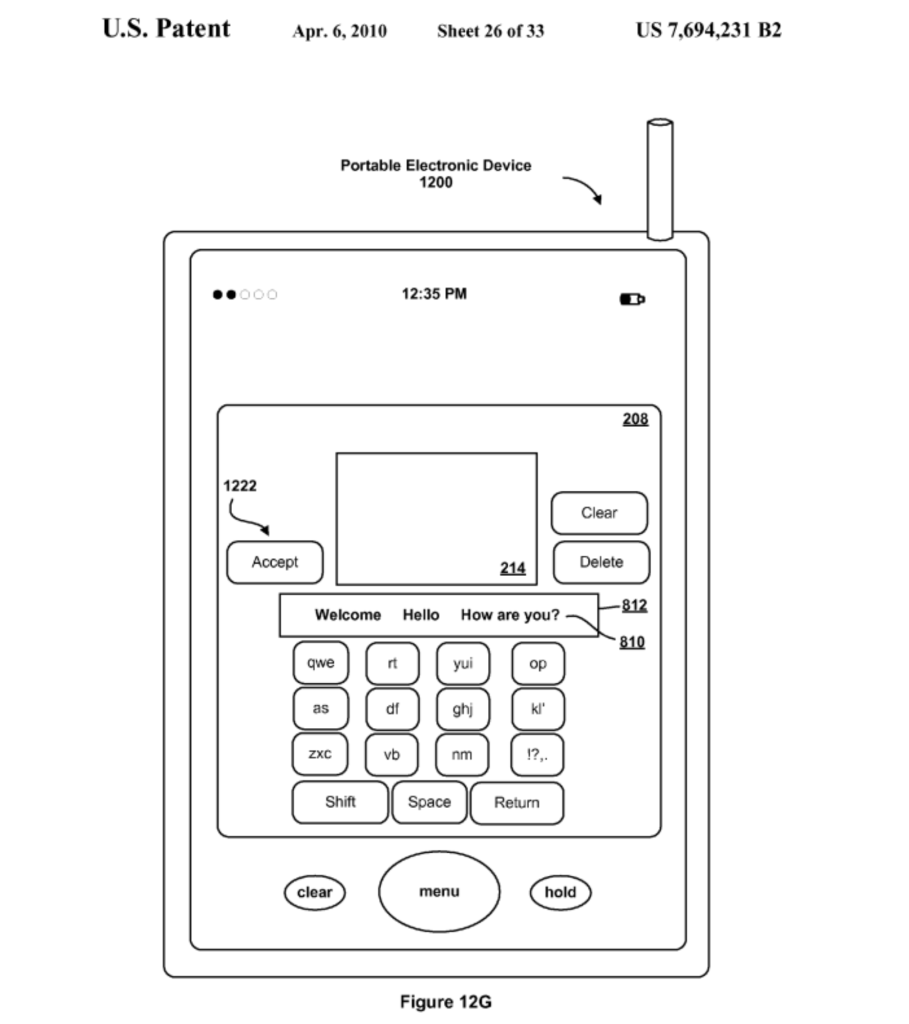

Kocienda’s “Bubble Keyboard” looked different from the others. The keys were larger but they had multiple letters on each. He tapped nonsense letters—“as zxc op rt rt space yui as space nm yul space nm as nm qwe”—and looked up. The screen read: “Scott is my name”.

“How did it know what I meant?” he asked.

Kocienda explained that the system used two dictionaries: a static one of common words and a dynamic one that learned a user’s personal vocabulary. “The purpose was to help you type words in your own voice,” he answered. “To give you what you meant instead of what you did.”4

Ken invented autocorrect to make a tiny touchscreen QWERTY keyboard usable.

But that invention did not happen in isolation. It happened because the leadership team set one clear priority, and because the team adopted a cadence of frequent demonstrations that produced constant feedback. This combination of clarity and rhythm made progress visible.

Thus ended the Keyboard Derby. Kocienda’s prototype became the foundation of the iPhone keyboard, and he spent the next year refining it, demonstrating progress at every step.5

Apple’s creative process was not mystical; it was transparent. And that transparency yielded two key insights:

1. They had no working keyboard. Leadership could see the criticality of this and created urgency to solve it.

2. Ideas to improve early ideas would come from the whole team if we gave them the opportunity.

With the culture of demonstrations, they make lots of things transparent:

- Backlog: make the keyboard work.

- Priority: everything else paused.

- Progress: demonstrated every other day.

- Method: build, show, learn, repeat.

- Rhythm: steady and relentless, making the work audible.

This is what transparency looks like in a creative process. It does not kill imagination; it channels it. The iPhone keyboard was not born from a single spark of genius but from the sound of a team learning in public.

When people imagine creativity at Apple, they often picture a lone designer, perhaps Jony Ive or Steve Jobs himself, sketching a perfect idea. That is a myth. Apple’s creativity was transparent and team-based. The iPhone in particular was a large team of teams. To maintain secrecy, very few engineers could see the entire product that was being developed, and many were genuinely surprised by features unveiled at the January 2007 keynote. Yet within each sub-team, the work itself was transparent. People could see their backlog, their priority, their progress, their method, and their rhythm.

That rhythm did not strangle creativity. It sharpened it.

Endnotes

- Laura Fermi and Gilberto Bernardini, Galileo and the Scientific Revolution (Basic Books, 1961), 4.

- Ken Kocienda, “Ken Koncienda Blob Keyboard,” Bluesky, March 30, 2025, https://bsky.app/profile/kocienda.bsky.social/post/3llmuxfgud22i.

- Ken Kocienda, iPhone Keyboard, U.S. Patent Office Patent US 7,694,231 B2, filed July 24, 2006, and issued April 6, 2010, 49, https://ppubs.uspto.gov/api/pdf/downloadPdf/7694231.

- “Duckin’ Autocorrect: The Inventor of iPhone’s Autocorrect Explains How It Works,” directed by The Wall Street Journal, 2022, 07:51, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ncj3QAKvBBo; “The Man Behind Autocorrect – Part One,” directed by Jerry Cuomo, 2024, 19:25, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9MVIrLUenm4.

- Ken Kocienda, Creative Selection: Inside Apple’s Design Process during the Golden Age of Steve Jobs, First Picador edition (Picador, St. Martin’s Press, 2019), 140–152.

1 thought on “The iPhone Development Process: Demonstrate progress constantly”

Comments are closed.